How-to: A Visit to an Iconic Bears Ears Site on the San Juan River

Words and photos: Andrew Dash Gillman

“Arthur is here,” she whispered. Her eyes and a subtle nod upward pointed to a lone raven soaring overhead along the canyon wall. The others looked up to confirm. Another woman showed gratitude. The corners of her mouth twitched downward, but her smile held. This woman had turned seventy, and this trip to Bluff was her birthday present to herself.

They were a small group of travelers in their sixties and seventies who joined the Wild Expeditions River House UTV Excursion. From Arizona, they have visited the Bluff area for years, but it was their first time booking a guided tour. I came to find out this visit was different in other ways as well, when I asked about Arthur later.

But for the moment, we turned our attention back to the thousand-year-old Ancestral Puebloan granary (a room used for food storage) tucked neatly into the sandstone.

How to an Iconic Visit Bears Ears Site on the San Juan River

The Wild Expeditions team actually leads two tours that access Utah’s River House ruins (site) on the San Juan River. The UTV Excursion, and the popular Kayak Hummer Expedition. The Kayak Hummer expedition is a full-day trip that combines the best of both southeastern Utah worlds: a river trip and an OHV trip. There are endless ways to have an incredible day adventuring among all the things to do in Bears Ears National Monument—but guests say this day is just about perfect.

I had scheduled just such a day, but a cold front brought overnight frost and created excessively chilly river conditions. The guides—Ian and Elle—consulted with the guests and switched to a round-trip UTV trip instead. No complaints. As the sun rose and warmed the orange-and-purple layers of the Cockscomb and set the cottonwoods on fire, we basked in its light. (It’s worth noting that throughout the season, such game-time substitutions are fairly rare. I booked deep into fall and the possibility of the change had been presented.)

Do not mistake the road to the River House for a typical road. Under most conditions, parts of it are less a road than a “route.” As in, the road that includes a short stretch of the infamously rugged route that pioneers from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints took in 1879 from Escalante to Bluff across 200 miles of sun-drenched, arid Colorado Plateau. “Infamous" meaning, the trip was supposed to take six weeks but actually took six months. Covered wagons are OG all-terrain vehicles but with none of the technology to make them particularly effective at it.

All this is to say that visitors should not take their rental crossover or passenger vehicle down the road to get to the River House.

In fact, while you’ll read reviews for every 4WD trail out there saying they were “surprised by how many Subaru Outbacks there were at the end,” you may also be wise not to take your Subaru on this road. We passed by trucks that had opted to park on the shoulder rather than attempt crossing a deep, wet wash.

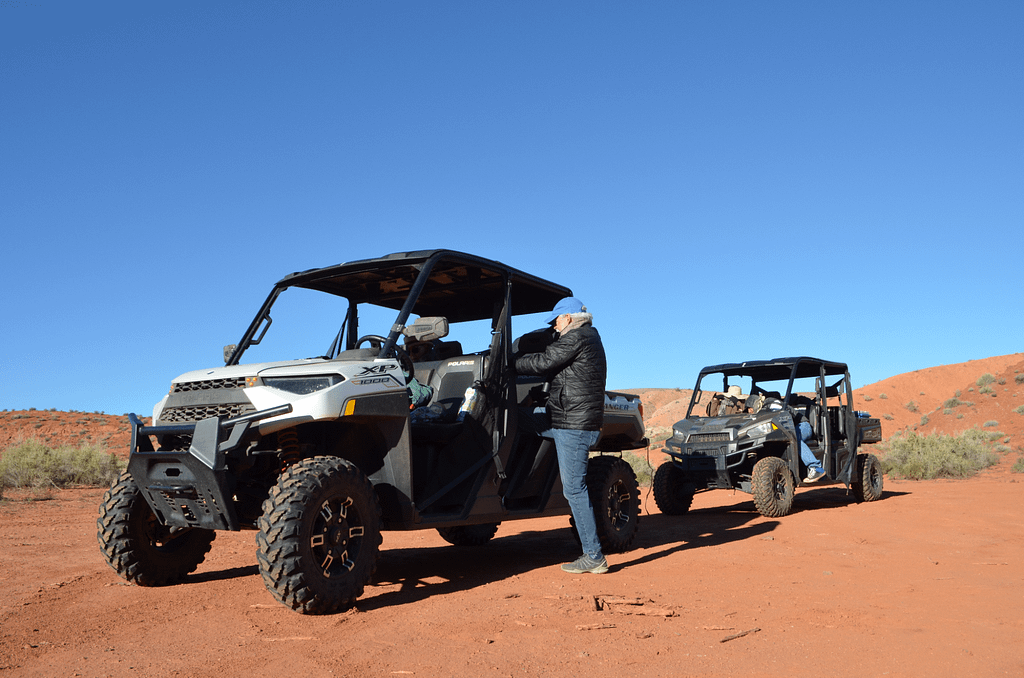

Enter Wild Expeditions’ UTVs. Utility Task Vehicles are built for the, ahem, task of tackling roads-in-name-only. Our guide clearly took pleasure in hitting the dips and divots, washes and washouts. The machine had modes for these things. Much, much nicer than choosing between the tentative crawl that leads to getting your car stuck or the YOLO ramming speed that leads to bottoming out and cracking the exhaust manifold.

River House Ruin Utah—A Site to Behold

But can we talk about the River House ruins? (Note: Increasingly, ruins are referred to as archaeological “sites” because of the negative connotation of “ruins.”) If you spend time exploring the wilderness canyons of Bears Ears National Monument, you will discover modest dwellings hidden in deep canyons, perched high atop rocky peninsulas like defensive citadels, and in places seemingly isolated and deliberately private (Read: “Awesome” Solitude: An Extended Hike in Bears Ears National Monument.)

River House, by contrast, has staked out a waterfront view, and rises like a watchtower over the San Juan River floodplain. From some angles, it looks almost carved out of the massive ridge the way Michelangelo found David by patiently chiseling away at a single block of marble.

If anything, it is more like additive sculpture, rock found or possibly quarried, collected, and carried stone by stone and plastered over with adobe mortar into sophisticated architecture: dwellings, kivas, granaries, life-sustaining settlements both natural shelters and defensive positions.

And with that tremendous view of the San Juan River.

But “sculpture” is not at all the right word for these structures just as “art” cannot convey the motivation of most pictograph and petroglyph panels. And a “view” of the San Juan River may well have been secondary or even a nonfactor when compared to the pure utility of the location alongside the land’s lifeblood.

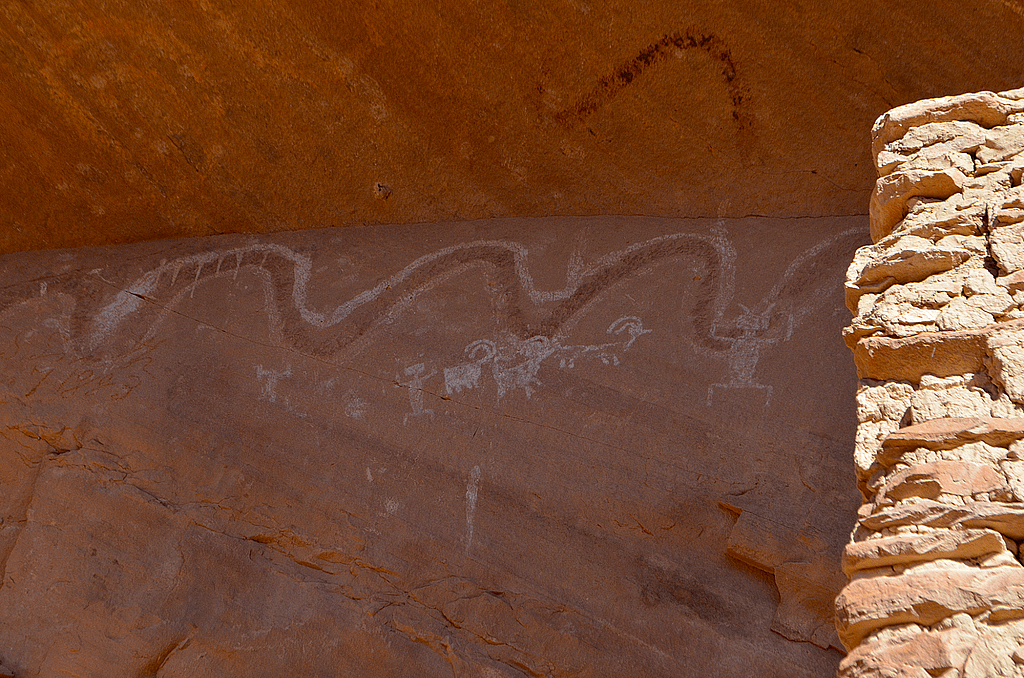

Still the pictures on the walls do tell stories. Wild Expeditions guide Ian, who is part Northern Italian and part Navajo, points to the winding, snake-like pictograph over the top of the site.

“There’s a reason that’s put there,” he said, his outstretched finger tracing the winding shape. “That giant serpent pictograph could also stand for the river but there’s actually some connection between that. Some of the Native American cultures that lived here believed that this San Juan River was once a giant serpent that slithered its way through and put a hole right in between Comb Ridge—the only natural cut in the ridge—before slithered down into what they call the upper canyon and kept going and made what we see now as Goosenecks [State Park].”

It’s a great story. Better, maybe, than the “entrenched meander” tale of a river and erosive forces patiently carving into rock over incomprehensible amounts of time. Stories can help us make sense of things, lending memory, human history, and cultural texture to our knowledge base.

Understanding Butler Wash “Kachina” Petroglyph Panel

Ian has many stories and a lot of local knowledge. For cultural reasons, though, he doesn’t make the short climb up to the Butler Wash Panel (also called the Kachina Panel). Here, the wall offers a record of information, ideas, and communications reaching back centuries, hundreds or thousands of petroglyphs spanning a deeply varnished span of sandstone, a canvas of rich desert patina built up from mineral deposits then carefully pecked away into images ranging from recognizable flora and fauna to unusual anthropomorphs and various symbols.

For the most part, any interpretation by us visitors is pure speculation and may fall utterly short of the original meaning and cultural significance. Elle leads the group storytelling here, drawing from things she’s heard, read, and researched and her multiple visits to the site, where she says she always sees something new or different on the dense wall and in the changing light. The kachina form itself is among the most famous and why the more formally named “Butler Wash Panel” often assumes the Kachina Panel nickname. Kachina is the word for an ancestral spirit being (katsina, from the Hopi kachi for spirit, life, life-bringer), of which there are hundreds in Puebloan culture. The large series of anthropomorphic figures appearing to wear headdresses are often understood as kachinas.

The panel cannot help but capture the imagination. Like this land’s earliest human visitors, we, too, tell stories. Our tools and platforms have changed (which means leaving these natural canvases exactly as you found them, even avoiding touching them), but the anthropological spark that motivates us to craft and share stories that can form emotional bonds persists.

Which brings us back to Arthur.

When Arthur passed away, these travelers spread his ashes somewhere near Bluff, among the wild canyons and mesas to which he’d led them on multiple tours in the past. Arthur had always been the tour organizer and guide. Perhaps that is partly why the group opted for a guided tour this time. And when they spread his ashes, a lone raven appeared in the sky and called out, and the connection was made.

Though Arthur the human, husband, father, and guide had passed on, he had not left them alone on this Earth, and their tireless guide and companion showed up in the sky, once again. We all tell stories. It seems the ones rooted in place are among the most meaningful.

Booking options:

—San Juan River & Cliff Dwelling Expedition

—Additional reading: Learning and Falling in Love with the San Juan River