‘Awesome’ Solitude: An Extended Hike in Bears Ears National Monument

Words and photos: Andrew Dash Gillman

We had both looked at the outside temperature on our phones that morning and briefly questioned our judgment. The thermometer had slipped to around 22 degrees Fahrenheit in Bluff, Utah, where I was warm in my room at Bluff Dwellings Resort and Spa.

My guide and hiking companion likely awakened to an even colder morning, a third of a mile higher at 6,100 feet, in nearby Blanding. But we were determined to hit the trailhead early to have plenty of time to enjoy serious solitude while connecting two key archaeological destinations on Cedar Mesa hiking Bears Ears National Monument before meeting up with a larger group. So we did what you do when hiking in the high country desert of southern Utah in winter: layered up. (See information about visiting throughout the year at the end of this story.)

Sunrise and the Vast Map of the Bears Ears Region

Southeastern Utah sometimes goes by the name of Utah’s Canyon Country. It is also part of the American Southwest’s Four Corners region. And southeastern Utah—true southeastern Utah in San Juan County south of Moab—is where you’ll find Bears Ears National Monument and its profound human and natural history. All these identities are intertwined. Indeed, at 2,215 square miles, Bears Ears makes up more than a quarter of San Juan County’s land and combines with the Navajo Nation (home to the Western icon Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park), and a handful of other national monuments, state parks, forest lands, and remote, wide-open space into a multi-use outdoor paradise.

It is, in a word, vast.

Given the immense geography, part of the reason for the early departure from Bluff Dwellings was we had around an hour’s drive to the trailhead. Things are just spread out down here. (But the drives are worth it!) So we set out before dawn.

And sometimes you can’t time something better if you try.

Dallin Tait, the personable general manager and guide at Bluff Dwellings and Wild Expeditions, inquired the night before if I’d be willing to start a half-hour earlier than originally planned, just to be sure we had enough time.

The objective was to hit the Fallen Roof Ruin trailhead on Cigarette Springs Road early enough so we could complete the 7–8 miles of Road Canyon to Seven Kivas before ascending the trail out of the canyon and up to the rim where we’d catch up with another group of hikers on the trail to the Citadel. The earlier departure meant we didn’t have to trail run, necessarily, but given the miles we would need to move at a brisk and continuous clip that more casual hikers might find too strenuous, particularly at elevation. It was not Tait’s normal pace with guests, but I was up for the challenge—which is to say I specifically got up for the challenge of a 12-mile day hiking Bears Ears National Monument.

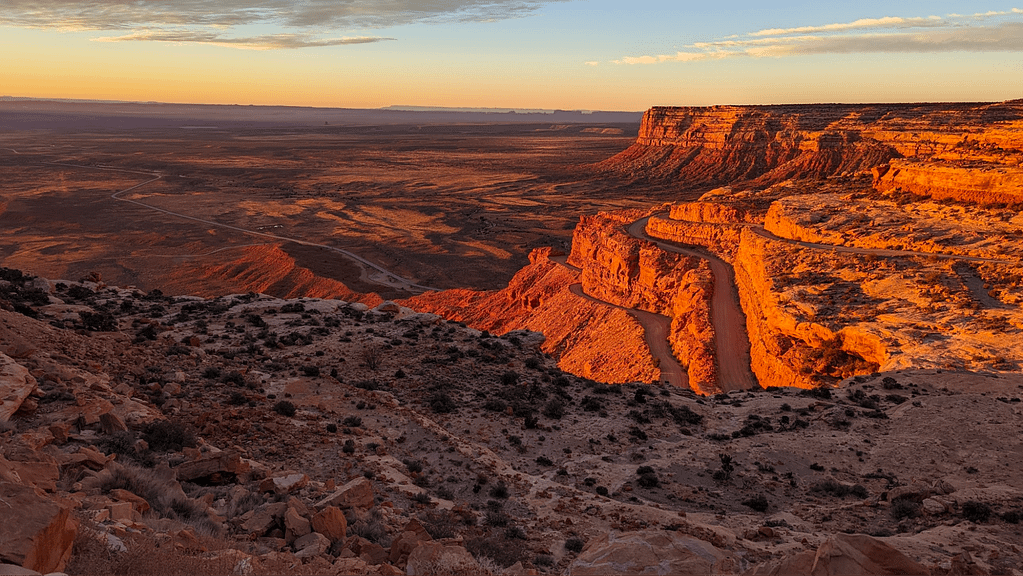

Thanks to that earlier departure, sunrise arrived at an ideal time. We were more than halfway up the steep switchbacks of the narrow gravel stretch of Utah Route 261 called the Moki Dugway when it became clear that we had to stop briefly to appreciate what the morning sun was doing to the expansive landscape.

Rising in the east, south of the distant Ute Mountain landmark, the first rays cracked the horizon and shot across the land, which was already blanketed by the gauzy morning light that seemed to awaken sandstone like the glowing Sankara Stones from Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom.

We saw the full palette of warm colors: the primaries of red, orange, yellow blended dreamily with peach, pink, and crimson, while the purples of the shadows gradually emerged into light. This is the time of day the Thomas Morans or Albert Bierstadts of the mid-to-late nineteenth century would surely have set up easel and put brush and paint to canvas to document the American West. Painters whose work hung in the U.S. Capitol and combined with black-and-white photographs, research, and lobbying to establish America’s system of national parks, starting with Yellowstone in 1872.

Sunsets are gorgeous. People know sunsets. Sunrises, however, can feel exclusive. You have to make a special effort to see them. But, sure as sunrises don’t last, we also had to get moving. Those miles, you know, wouldn’t hike themselves.

The Hike into Road Canyon

At the trailhead we double-checked our day packs for water, snacks, navigation resources, and a few other essentials. The sun had brought a few more degrees with it so we adjusted layers, knowing we could always add or subtract along the way as needed. Once we got moving we’d surely warm up further.

Once comfortable, we took to the trail quickly, descending down the canyon into the depths of wilderness.

Nearly all the twelve miles we covered took place in the Road Canyon Wilderness Study Area. (All except for a square of Utah Trust Land.) WSAs are like a junior varsity subcategory of America’s collection of National Conservation Lands that meet the criteria for full-fledged Wilderness Area designation—that is, “minimum size, naturalness, and outstanding opportunities for recreation”—but require Congressional action to achieve that status.

Remote, wild, pristine, beautiful: these are some of the words that come to mind.

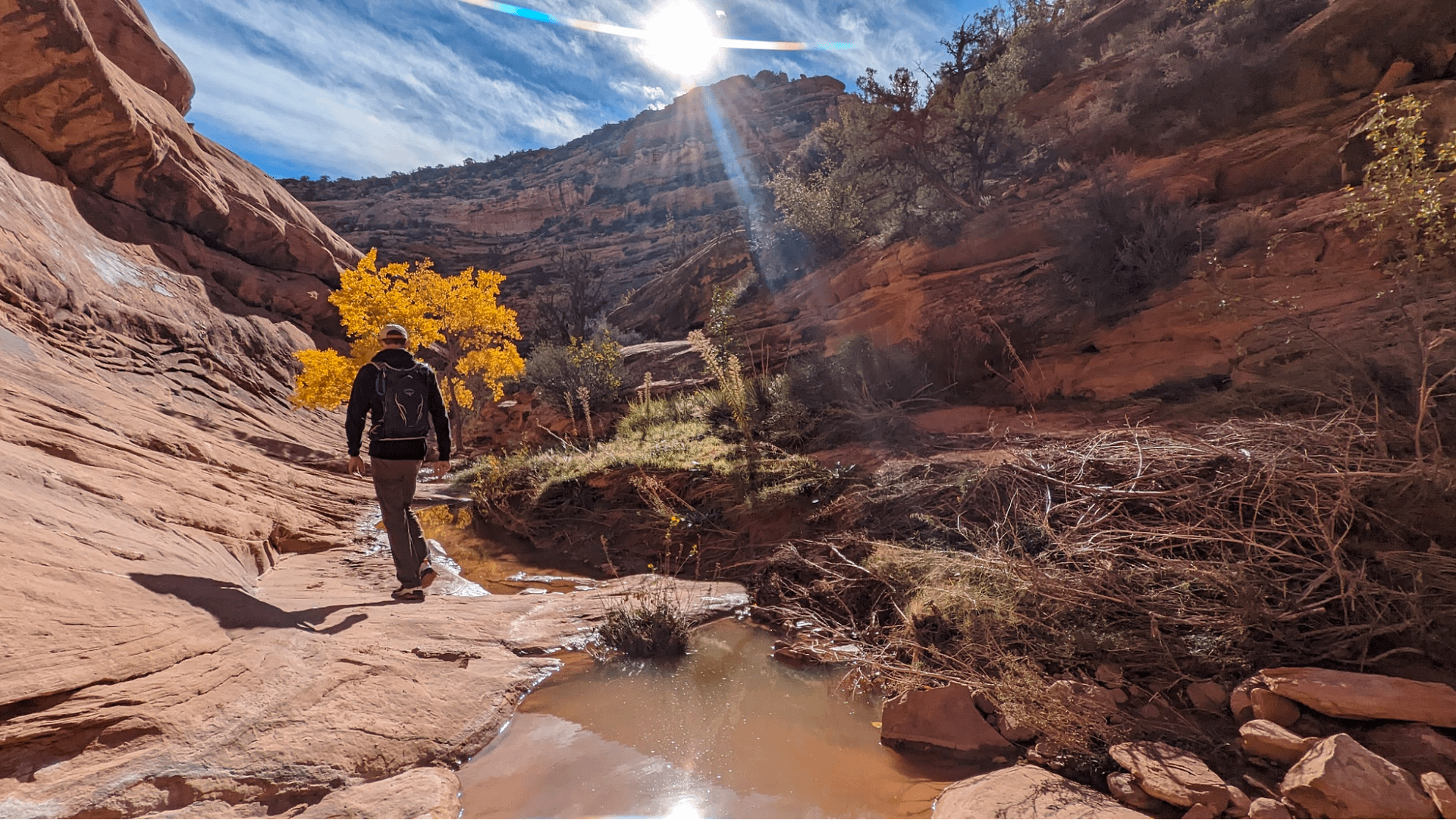

The scenery pops with every step—sometimes quite dense desert ground cover and hearty shrubs mix with the region’s characteristic pinyon-juniper woodlands, which somehow make a decent living in harsh environments. When I visited in late November, the sporadic cottonwoods sheltered low on the canyon floor still boasted a leafy canopy of brilliant yellow. As the sun continued to rise, its light bounced around and filled the canyon, eventually finding its way into the soul of the sandstone. The whole scene makes it difficult not to stop frequently to photograph or just take it all in. And we can’t help but make an exception for just that when the landscape casts its colorful reflection in the very catchpools that water the cottonwoods and nourish the canyon, shallow remnants of a recent storm.

What to say of the hiking itself? The first half of the hike felt like a near-continuous, but gentle descent, with a short climb up to the bench of the sensibly named Fallen Roof Ruin and, later, the awesome Seven Kivas. Indeed, we dropped some 900 feet over 5.5 miles. I could meditate for pages on the ancestral sites themselves. I picked the word “awesome” deliberately—not the word popularized in the 1908s, but the original sense of “filled with awe” or, better, “profoundly reverential.” Indeed, the BLM and U.S. Forest Service's historic co-management of the monument with the five tribes of the Bears Ears Commission reflects the land's rich cultural heritage. Many within those tribes continue to rely on these lands for traditional and ceremonial uses.

The history alone is worthy of extensive research. Briefly, the structures date back to the early Pueblo periods, when houses, kivas, roads, pottery, and an array of increasingly advanced tools and agriculture emerged, maybe 850 to 1,100 years ago.

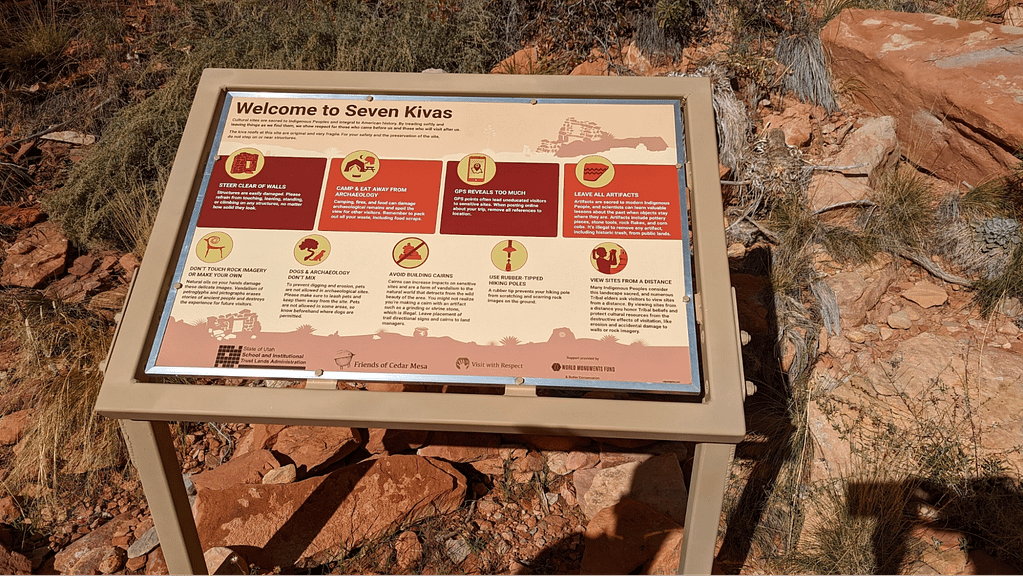

Every surviving potsherd is a gift to the present and a symbol of deep cultural roots, let alone entire walls, dwellings, granaries, and ceremonial kivas of stacked sandstone, clay, silt, reeds, and sticks or timber. Some walls look impermeable, while crumbling remnants of others remind us how fragile this human legacy is. It’s easy to wonder how much we’ve already lost and to hope that modern campaigns of Leave No Trace and Visit With Respect are heard and followed. Because that’s not always true, it’s no wonder the area’s stewards caution visitors that “GPS reveals too much” and ask people to remove references to locations to prevent uneducated visitors from wreaking havoc, whether intentionally or unintentionally—and the land managers will tell you they frequently see both.

We tread lightly out of an abundance of caution and respect.

The Privilege of Visiting Ancient Places

Our morning continued with an ascent out of the canyon to the Road Canyon Rim Trail. We had one false start up a potential route but checked our GPS and continued back up a different drainage a little ways to find the actual path back to the rim. It’s a reminder of the importance of frequently checking your position and, of course, bringing the tools to be able to do so. Still, there aren’t all that many ways up the otherwise steep canyon walls. It’s just finding the best way. On this part of the trail, I am acutely aware of the likelihood of following in ancestral footsteps, a consequence of the more methodical pace that comes with gaining more than 400 feet in under half a mile. (I also took the time to remove another layer—by now it’s practically t-shirt weather.)

We’d hiked about 7.5 miles and figured we’d catch up with the larger tour group in another half-mile or so. In many ways, the morning trek was about experiencing the best of this wilderness—indeed, this capital “W” Wilderness—in solitude, moving quickly across the rugged landscape to connect trails, passing through the even lesser-trekked stretches of already minimally traveled paths.

So maybe these hikes and lands aren’t for everyone. That may be true of wilderness and even the wilderness ethic. And sometimes just being able to go up to the edge of wilderness matters, because for what it means that wilderness still exists. That idea paraphrases Wallace Stegner and it’s a sentiment that rings true out here. There are overlooks at the rim trail to the magnificent Citadel (magnificent because I can’t use awesome again, can I?) that Wild Expeditions guides can get virtually anyone too. And many families with children of most ages can find an exquisite outdoor recreation and archaeological experience at the Citadel with preparation and a permit or, better yet, a guide.

But I needed the distance and pace to push deep into the heart of wilderness, to have worked for the privilege of visiting ancient places, some with a cultural significance that Western vocabulary doesn’t really capture. So I appreciate what I can and am okay by not having the words to comprehend everything, if anything.

After a few more minutes we hear the excited voices of young children carry across the plateau. It sounds like lots of children. “This ends the quieter portion of our hike,” Tait comments with a laugh. That’s okay. I’ve had my fill of solitude today. Besides, now I’ll get to hear and see the landscape through entirely different eyes.

How to Visit Cigarette Springs and Road Canyon

While this story highlights an extended strenuous hike, there are shorter out-and-back hikes to both Fallen Roof and Seven Kivas as well as the iconic Citadel, to be featured in another story. But all of these hikes are remote and require some preparation. If you choose not to book a guided tour with Wild Expeditions, there are a few things you should know about visiting Road Canyon.

- When open, the Kane Gulch Ranger Station on Utah Route 261 is a great stop to orient yourself to Cedar Mesa. (March 1–June 15 and Sept. 1–Oct. 31 from 8 a.m. to 12 p.m. daily.)

- Cigarette Springs Road is 9 miles south of the ranger station.

- A permit to hike or backpack Road Canyon is required. Permits range from $5/person for a day to $15/person for a backpacking trip. Annual passes available. Both access points to Road Canyon are unmarked and the second is a 0.8-mile high-clearance only road that can be hiked. More information.

- Validate permits in person when hiking Bears Ears National Monument in the peak seasons. More information.

- There are no maintained trails in Road Canyon. Routes generally follow the mostly dry creek bed.

- In the summer and winter, information on visiting this area can be obtained by visiting the Monticello Field Office or calling the Cedar Mesa Permits Desk at 435-587-1510.