Discovering and Defending the Citadel

Words and photos: Andrew Dash Gillman

No cuts, no butts, no coconuts.

I don’t know the origin of this phrase, but I will now forever associate it with a hike to the Citadel, the categorically iconic Cedar Mesa trail in Bears Ears National Monument. I was part of a permitted group of 12 making the trek that day with the guide services of Wild Expeditions, a group that included kids aged 4–16 as well as one dog—who needed a little help down a ledge someone had bridged with a dead juniper. We were marching single file down the narrow path through the cryptobiotic soil on the return hike, keeping individuals from passing one another or, rather, butting in front of someone, as one of the younger kids sought to prevent with the repetition of the phrase.

And that’s okay.

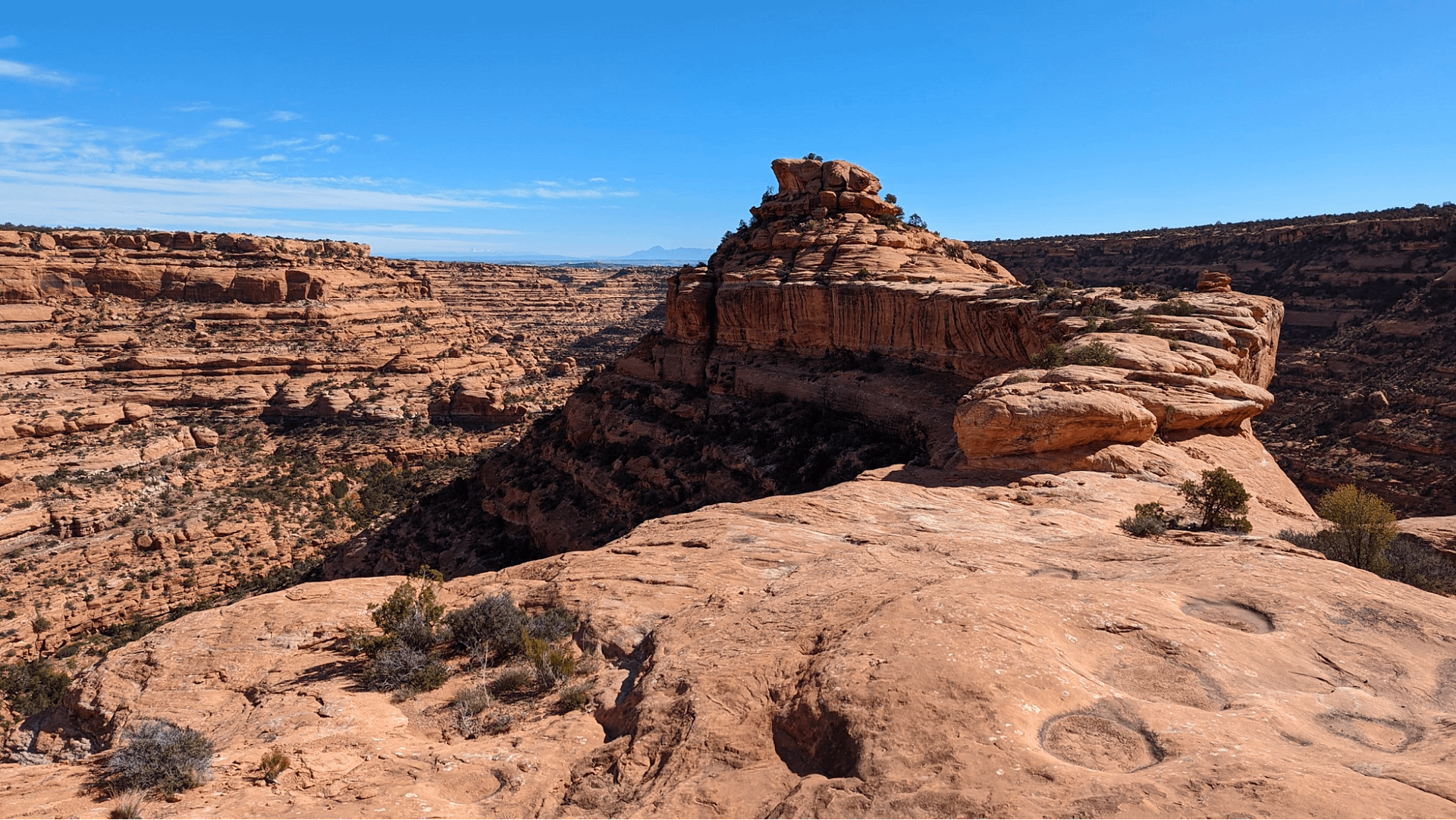

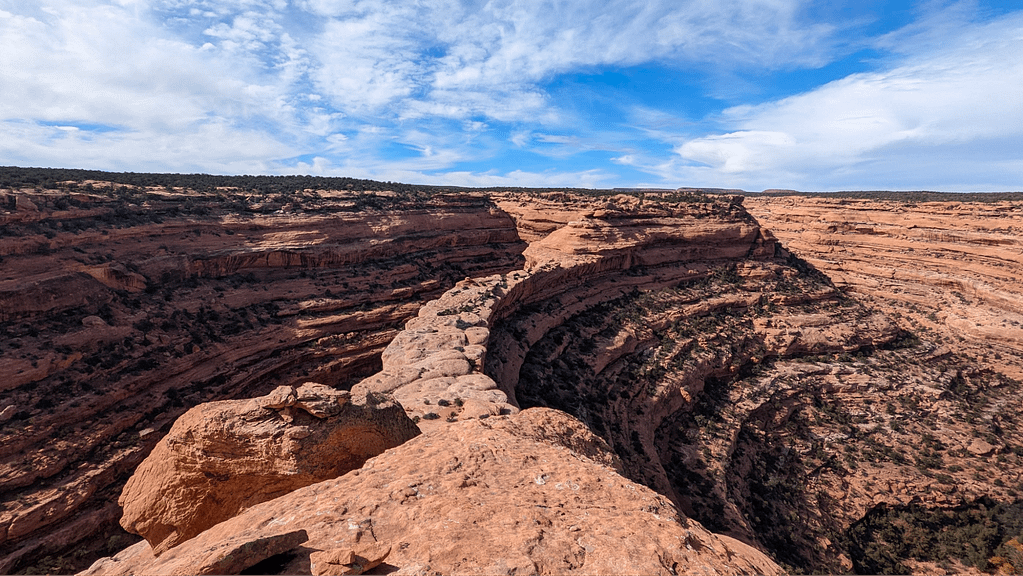

Better to avoid cuts, butts, and coconuts than to trample the delicate soil. It’s one of many inspiring lessons in ecology and history learned on this fascinating hike. And one reason I think it’s iconic. That, and its stunning land bridge with a sheer drop on either side, perhaps a more obvious reason the Citadel in Bears Ears rivals the likes of Angels Landing in Zion National Park.

Finding the Trailhead

As with all the best hikes in Bears Ears, one of the absolute top ways to get the most out of a visit in terms of worry-free access and local knowledge is by traveling with a guide such as my Wild Expeditions Bears Ears tour. Citadel proved to be no exception.

The trailhead to Citadel starts at the end of a very rough road after a turnoff from a road that is, at times, also very rough. This detail is to say that permitted visitors in high-clearance, 4WD vehicles will get a hike that is a little over four miles, round-trip. Regular passenger vehicles may have to pull over somewhere shy of the 6.1-mile turnoff from Cigarette Springs Road adding between 0.6 of a mile to a mile each direction. All doable, just worth noting. If it’s been raining, all bets are off. You can check conditions when you stop at the Kane Gulch Ranger Station to have your permit validated when visiting in the spring and fall. (For hiking Cedar Mesa Utah, read about permit requirements.)

"This is a hike that’s in the heart of the heart, deep, premier wilderness, with very little comparison in the lower 48 states."

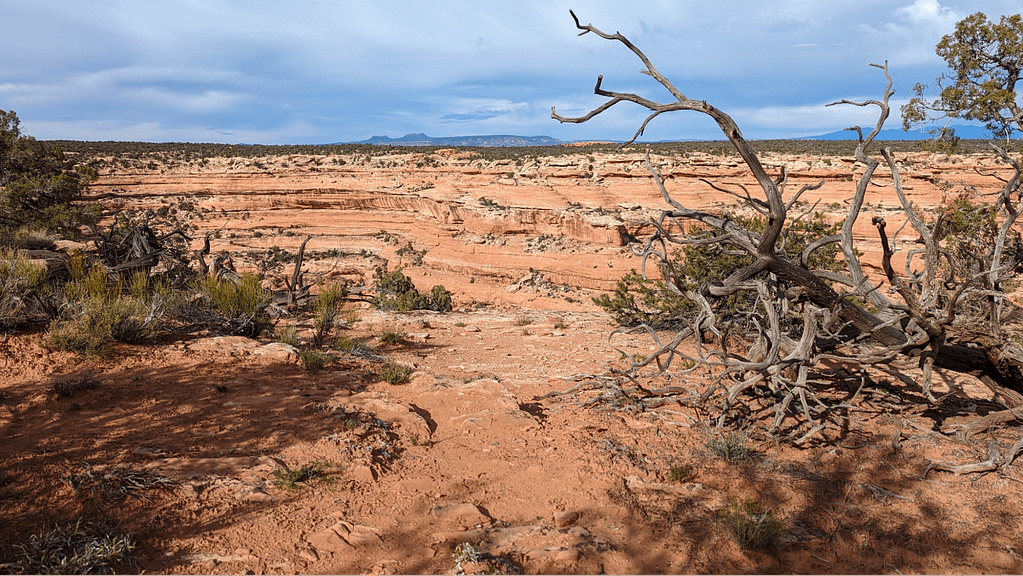

But I’ve skipped ahead. Let’s zoom out a bit. Way out. State Route 261 bisects Cedar Mesa approximately down the middle, running for 34 miles between S.R. 95 in the north near Natural Bridges National Monument and U.S. 163 near Goosenecks State Park and Valley of the Gods, in the south. Cigarette Springs Road is about in the middle, around 19 miles from the U.S. 163 turnoff. Cigarette Springs cuts deep into the heart of Cedar Mesa. This is a hike that’s in the heart of the heart, deep, premier wilderness, with very little comparison in the lower 48 states.

OK. Let’s zoom back in.

The Hike to the Citadel, Bears Ears

The hike starts with that friendly meander across the mesa top and along the rim of Road Canyon. Stay on the existing trail to protect the crust but remember to look around. A couple of vantage points into the rim within the first half-mile reveal the Seven Kiva Site, on the opposite side of the canyon, on a bench near the canyon floor. It’s one reason you might want to carry binoculars.

The trail then crosses a wide stretch of classic Southern Utah slickrock. After the confines of the first mile, there’s some freedom to spread out a little on the mesa, but watch for the quintessential cairns—small stacks of rocks that mark the way—to stay on course, because they’ll guide you to the point where the trail makes a somewhat tricky descent from the mesa top down its cracked and sloping southern face. Some people may not be able or willing to complete stretches of the trail if they are unsure or unsteady on scrambles or that aforementioned dead tree portion. In these remote parts of the country, the trails don’t get the TLC as our national parks, which is part of what makes them special, and more limited in appeal.

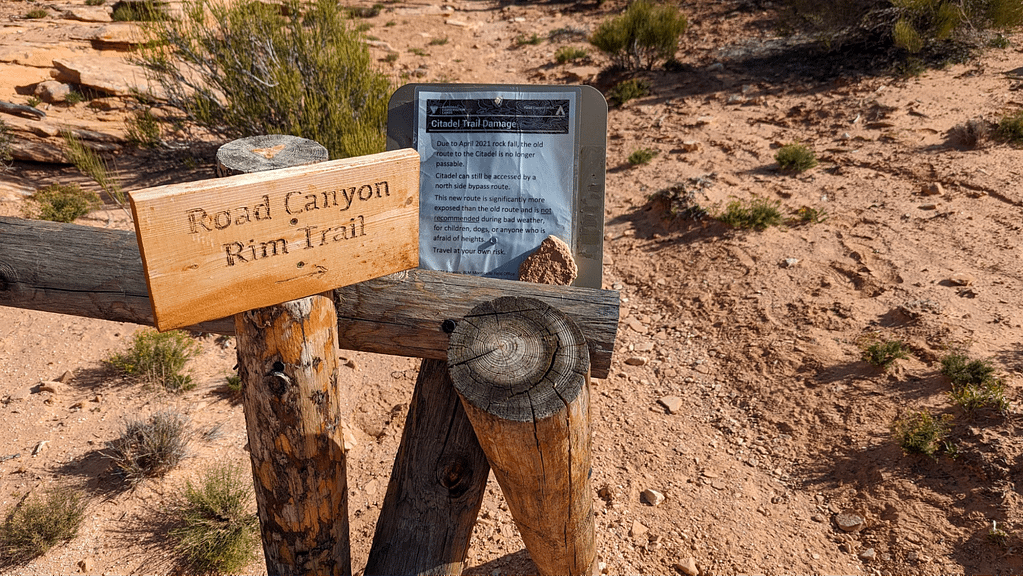

Truth is, there are parts of this trail that have changed. Jared Berrett (co-founder of Bluff Dwellings Resort and Spa and occasional guide at Wild Expeditions) points to a boulder—really, a chunk of the canyon rim the size of a small house—and explains how they once stopped for a picnic in its shade, back in the days before the forces of weather and time dislodged it in April 2021 and it crashed to the ground, changing the landscape and the route.

There’s one more grand viewpoint before the land bridge that provides an incredible angle out onto the peninsula and into the surrounding canyon—canyon that cuts around 500 feet down and wrapps some 330 degrees around the point.

Here again, some hikers may opt to end their journey with this view given the next quarter-mile. This stretch starts with a careful descent (some choose to scoot on their hands and butts in a kind of crab walk) before leveling out and briefly opening up at the top of the funnel to the land bridge. While not nearly as narrow or steep as Angels Landing (where the National Park Service wisely installed chains to provide added security for hikers), it is still prudent to mind your step and watch the little ones. Finally, the bridge reaches the knob at the end of the peninsula and its short scrambles up to the object of this hike.

The Destination

So far, I have withheld describing the Citadel site. When I hiked it, I confess to only having a vague notion of what I was going to see. I had seen the cover of the September 2022 National Geographic, so I knew something of the setting. And I knew we were hiking to an ancient site. But I had put my trust in the tour guides and didn’t do any additional research. It’s weird to think about going somewhere without that picture in your head—you know the one, the one you saw in your Instagram feed or For You Page on TikTok that made you believe you needed to see that place for yourself, maybe even take a picture in the same place to show you were there.

While there has been a healthy debate in recent years over the impact of social media on destinations and, in particular, on our public lands when a once-obscure (what some would say, once “protected,” though that might be labeled “gatekeeping”) place goes viral, powerful words and alluring pictures have long provided the initial impulse and spark for travel.

In a chapter on landscape in The Art of Travel, British author and philosopher Alain de Botton described poetry by William Wordsworth that had been inspired by late-eighteenth-century experiences in England’s Lake District. Within a couple of decades, Wordsworth’s work created a tourism destination of the district among the nation's leisure class who wanted to follow in Wordsworth’s footsteps and experience a restoration in nature. Earlier in the book, de Botton described his own experience with a travel brochure photo of a palm tree that ended up landing him in Barbados.

All this is to say that it’s tempting to resist describing or sharing images of the Citadel site, even in an age where that information is readily discoverable online. Perhaps the best we can do is recommend not posting GPS coordinates and educating visitors how to visit responsibly and respectfully.

"Between minding my step and the canyon views, I realized I had forgotten to do something. I had forgotten to look up."

For me, having a guide meant I didn’t have to take my usual precautions of carefully researching and cataloging the trail to know its features and know exactly what I was looking for—I didn't have to over-prepare for the unknown. I simply had the map downloaded to an app on my phone and the essentials in my daypack for the journey. I could hike with full attention.

And yet, when we completed a scramble and cleared a ledge, a casual comment by Jared asking if I’d seen it yet caught me off guard. Seen it? Between minding my step and the canyon views, I realized I had forgotten to do something. I had forgotten to look up.

Woah. Where did that come from?

From below, the Citadel site is perfectly imposing. A seemingly pristine wall of sandstone and adobe mortar with four or five rectangular cutouts for windows or crawl access. It seemed almost to “hold up” a thick slab of deeply layered sandstone overhead. Finding my footing and using my hands, I complete the scramble and carefully approach the site. On closer inspection, the integrity of the architecture holds up. The walls of the structure, enduring though assuredly fragile, the details of the construction, the thumbprints in the adobe, the lintel above the window and the smoothe, flat sill, each piece found or quarried and hauled up to this site. Wooden fixtures still embedded into the openings held together through the centuries with dried grasses, reeds, branches, sumac, textile-like bark of trees.

After seeing the construction up close, it’s difficult not to look for it in nature when hiking in the area. Of course, not everything remains intact. The crumbling easternmost portion of the structure serves as a grim reminder of its age and fragility.

In Defense of Place

“Citadel” is a word for a fortress, a defensive command point often at high vantage. So it certainly checks all those boxes.

We observed short arcs of scattered rocks with a few still seemingly deliberately stacked at the edge of slabs looking back west across the land bridge. It is easy to imagine taller walls as additional lines of defense at this lookout. It’s an interesting hypothesis given the dwelling seems perched improbably high and isolated for an extended stay—at least compared to dwellings found on benches closer to the canyon floor, where residents would have better access to water and food sources and the other structures in their network, the kivas and great houses for ceremonies and gathering, and granaries for food storage.

But then, some dwellings in the greater Four Corners region are tucked rather incredibly into alcoves on sheer cliff walls with treacherous ingress and egress.

The archaeology of Bears Ears is a big part of what makes the monument so significant and so important to the five tribes who help oversee its management. For those of us who are just passing through, temporary travelers and visiting stewards of the land and its history, archaeology is also the story that draws us there. It’s a mystery we can’t fully solve.

For some of us, our time on this planet is a mystery and we spend our days balancing the things we need to survive (sleep, eat) and the work we need to be economically viable, with, hopefully, a healthy measure of actual living, pursuing the things that bring us joy, peace, gratitude, sense of well-being, or whatever it is that makes life worth living. When we approach an ancient cliff dwelling, it feels to me that it should be impossible for us not to stop and consider what life was like or to learn from our guides or our research what they needed to survive, let alone to live. How did these ancient people view themselves within their universe? What did they know and understand that we don’t and vice versa?

After an exploration around the full expanse of the Citadel site, we return the way we came. While I might usually settle into deep introspection about my experience, I welcome the energy and enthusiasm of the children in the group, chattering on the return hike with all but the littlest one (asleep on her father’s back) making the two miles back with ease. It is here that the kids regularly caution us against butting or cutting. The presence and ease of the youngest hikers on the landscape reminds me how adults often regard kids in the rock climbing community. They are fearless and natural climbers, they quickly solve what climbers call “problems,” and make games out of every challenge and adventure.

If I had grown up on this mesa or in these canyons, learning to navigate by story and stars, getting everything I needed to live from the surrounding lands, I would surely have a very different physical relationship with the space. The story would change. What would the children chant as they crossed the mesa? Take away all our names—Citadel, Road Canyon Wilderness Study Area, Cedar Mesa, Bears Ears—or, indeed, Bears Ears in other languages Hoon’Naqvut (Hopi), Shash Jaa’ (Navajo), Kwiyagatu Nukavachi (Ute), Ansh An Lashokdiwe (Zuni)—what remains? Land. Open sky. Wind. Water. A rugged, remote, once life-sustaining expanse of mesas and canyons. An entire world. A world that, standing atop the Citadel, was clearly worth defending.

For more information about visiting sensitive archaeological sites responsibly, read through helpful Know Before You Go planning resources.

Book a custom, private day-hike with Wild Expeditions.